When Floods Are a Blessing: Australia’s Floodplain Graziers

We’re all familiar with the devastation floods can bring to Australian farmers—livestock losses, damaged infrastructure, isolation from essential supplies. But there’s another side to flooding that doesn’t often make the headlines. In certain parts of Australia, annual inundation isn’t just tolerated; it’s eagerly anticipated. For graziers in these unique landscapes, floods mean life, not loss.

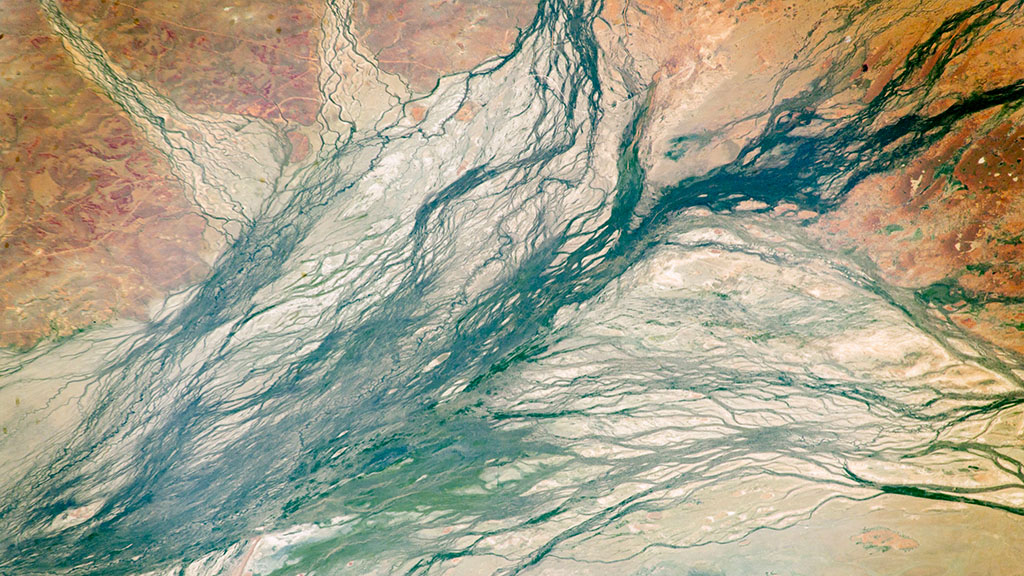

The Channel Country: A Desert That Floods

This remarkable region, covering roughly a quarter of Queensland, is essentially a desert that floods. It sits in the Lake Eyre drainage basin, where rivers flow south from heavy rainfall hundreds of kilometres to the north, spreading water and nutrients across millions of hectares of otherwise arid floodplains.

When the channels flood—which happens irregularly, sometimes with years between events—the transformation is extraordinary. Water can spread up to 30 kilometres wide as it snakes along ancient braided channels. This natural irrigation brings life-giving water and nutrients to the Channel Country, as it has been doing for millions of years.

For Channel Country graziers, these floods are the foundation of their pastoral operations. Cattle are moved back onto the floodplains a couple of months after waters recede, when the plains are bursting with vegetation. This flood-generated feed imparts a distinctive depth of flavour to the organic beef produced in the region—genuinely seasoned by nature’s cycles.

The timing can be bittersweet, though. While Channel Country producers celebrate the arrival of floodwaters, they’re often aware that the same water system has just caused devastating losses to graziers further north. It’s a reminder of the dual nature of flooding in Australia—destructive in some landscapes, essential in others.

Macquarie Marshes: Where Cattle and Waterbirds Thrive Together

Moving south to New South Wales, the Macquarie Marshes tell a similar story. Covering approximately 200,000 hectares, these marshes are among the largest semi-permanent inland wetlands in the country. They’re internationally significant under the Ramsar Convention and support over 80 waterbird species.

What makes the Macquarie Marshes particularly interesting is the sustainable coexistence of cattle grazing and environmental conservation. Beef cattle production on floodplains and in wetlands flourishes as a result of flooding, and much of the marshes are owned and managed by private landholders predominantly engaged in livestock production.

These floodplain graziers have protected waterbird breeding colonies on their properties since settlement. The marshes represent the most important colonial nesting waterbird breeding site in Australia for species diversity and nesting density. When flooding occurs, it creates the precise conditions needed for both cattle feed and bird breeding habitat.

Northern Floodplains: Kakadu’s Seasonal Rhythms

In Australia’s tropical north, Kakadu National Park showcases another flooding pattern entirely. Here, the wet-dry tropical climate drives seasonal flooding across vast floodplains. The relationship between flooding and plant growth follows patterns that Aboriginal people have understood and worked with for millennia.

The seasonal inundation supports an explosion of plant growth during and after the wet season, which in turn supports diverse wildlife populations. While Kakadu is primarily protected for conservation, the broader principles of flood-dependent ecosystems apply to pastoral lands across northern Australia where seasonal flooding creates productive grazing opportunities.

The Murray River Floodplains

Along the Murray River system, floodplains like Barmah-Millewa and Chowilla demonstrate how flooding maintains productive landscapes. These areas contain the world’s largest river red gum forests and support diverse ecological communities that historically sustained both Aboriginal people and, later, pastoral operations.

Chowilla had 150 years of continuous stock grazing before the pastoral lease was relinquished in 2018. While grazing has now ended in this reserve for conservation reasons, it demonstrates the long history of floodplain pastoralism along the Murray system.

The challenge with these southern floodplains has been river regulation. Natural flooding that once occurred about 45 times in 100 years now only occurs about 12 times in 100 years. This reduction has dramatically altered both the ecological character and the productive capacity of these lands.

Why Flooding Matters for Production

So, what makes flooding beneficial for grazing? It’s straightforward biology. Floods carry nutrients from upstream catchments and deposit them across floodplains. They recharge soil moisture in arid and semi-arid regions where rainfall alone is insufficient. The combination creates pulses of productivity—the “boom and bust” cycles that characterise Australian inland ecosystems.

For cattle, this means high-quality feed that wouldn’t otherwise exist in these low-rainfall regions. The nutritional value of flood-generated pasture is exceptional, producing premium-quality beef that commands market recognition.

Looking Forward

Understanding beneficial flooding is increasingly important as Australia grapples with water allocation decisions. While we rightly focus on protecting communities and infrastructure from destructive floods, we also need to recognise that some Australian landscapes and industries depend on regular inundation.

The Channel Country graziers, Macquarie Marshes landholders, and other floodplain producers are working with ecological processes that have shaped the Australian continent for millions of years. When managed sustainably, these flood-dependent pastoral operations represent a uniquely Australian form of agriculture—one that works with, rather than against, the rhythm of the land.